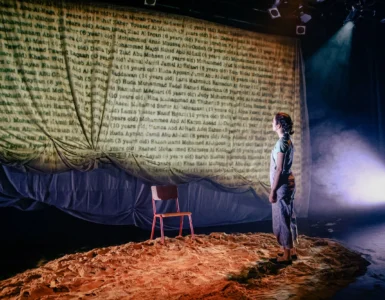

This year, Binge Fringe contributor Lamesha Ruddock, in collaboration with Blemme Fatale Productions, launched the Black Performers’ Awards to celebrate the achievements, contributions and quality of work presented by Black performers at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2025.

The largest international performance festival in the world, the Edinburgh Fringe is a kaleidoscopic marketplace of entertainment, each year making seismic offerings to mainstream culture. In 2025 alone, a staggering 2.6 million tickets were issued to 3893 shows, drawing in over 1770 producers, programmers, bookers and agents from over 68 countries. It’s a festival that prides (and brands) itself as at the vanguard of the arts, ushering in waves of fresh thinking year on year. It is supposedly the ultimate harbinger of the culturally cutting-edge.

Yet, Binge Fringe’s awards remind us that the festival’s historically white and heteronormative legacy casts a long shadow over the present – a history marked by the exclusion, tokenisation and pigeonholing of artists of colour and their cultural contributions. In recent years, both the festival and local authorities have made efforts to prioritise ‘diversity’. This has come in the form of providing partnerships and grants to initiatives such as the EdFringe With Spice Guide by LULA.XYZ, supported by the City of Edinburgh Council, Culture and Wellbeing Services, Diversity and Inclusion. This comes alongside the establishment of other initiatives like Jess Brough’s Fringe of Colour – a database and ticketing system dedicated to PoC artists. Yet, despite schemes designed to counter the negative bias of non-white stories at the Fringe, it raises the question of why it has taken so long for the work of PoC artists to be formally recognised and awarded.

The arts’ access problem is an already well-trodden topic – extortionate Fringe prices in the city make it difficult enough for any artist to bring work here in the first place. But that Lamesha’s awards are among the first of their kind reflects an issue at the epicentre of the festival. On a systemic level, there is the unspoken consensus that whiteness is an unchanging, default characteristic of the festival, one that is exacerbated by the selective arbiters of accolade.

This summer, I worked in the Press Office of one of the Fringe’s largest venues, which hosted one of the most artistically diverse programmes at the festival. Daily, I interacted with artists, critics and journalists, observing the flow of characters who drift in and out, striking up conversations with people from various walks of life, and generally immersing myself in the flurrying discourse of the press. 2025 saw the highest number of accredited journalists in the festival’s history, attracting 718 reviewers and critics. Whilst there are no statistics analysing the demographic of reviewers, my own observations from inside the festival revealed a striking proportional discrepancy.

Out of the multitude of accredited media individuals I worked alongside throughout the festival, I only briefly encountered two who were PoC. For the most part, I was immersed in a pool of white, male, older reviewers. As a mixed race 20-something-year-old, I was disappointed but not surprised. It feels all too familiar and ironic to work at a festival that was supposedly championed for its breadth and inclusivity.

There is a gaping disconnect between the types of shows on offer and the demographic of accredited media available to review them. Within the Fringe ecosystem, performers, critics and audiences exist in symbiosis. Where efforts might be made to ensure culturally diverse programming, the majority pool of white, male reviewers persists as the dominant gatekeepers and tastemakers of culture. In short, a show’s success still very much depends on what a boy’s club of revered critics say about it.

And even when a PoC show might receive critical acclaim, it’s still received within the narrow parameters of acceptability or taste established by said select group. “Be marginalised, but only in the way we want, in a way that doesn’t make us feel uncomfortable, in a way that we can recognise”. Being a ‘marginalised voice’ becomes its own predetermined category. To what extent does ‘marginalised’ remain a useful or productive term, and when does it become limiting?

There seems to be a lack of urgency for change, and a blindness to the festival’s disproportionately white tastemakers. If the Fringe truly wants to champion diversity, then it needs more diverse reviewers. It requires reviewers with intersectional sensitivities and those who have a lived experience of the show they are reviewing. It needs to value a range of critical perspectives and move away from fawning over the reductive star rating of a select few. This requires a sector-wide commitment, not one that comes exclusively from those disadvantaged.

To those critics who say that ‘diversity’ is tokenistic, I say – it’s okay if you didn’t like the show. But maybe consider the fact that the show was simply not meant for you.

Photo Credit: Jim Divine on Unsplash