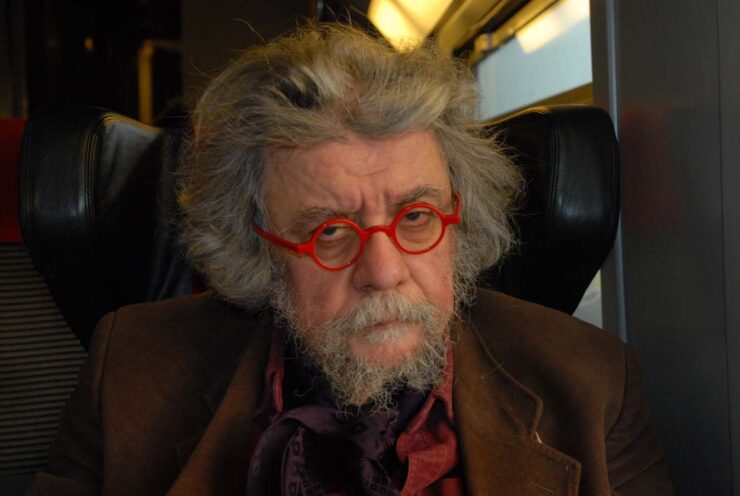

Philippe Gaulier taught thousands of students in his lifetime. From Paris to London to Étampes, via Montreuil and Sceaux, a peculiar pilgrimage unfolded for over four decades. Performers crossed oceans not to be praised, but to be told, quite plainly, when they were not funny, by clown pedagogy’s most charismatic executioner.

In the days and weeks following Philippe’s death at the age of 82 on the 9th of February 2026, there have been no shortage of tributes, recollections, and reckonings. Each will attempt, in its own way, to articulate what Philippe meant to those lucky enough to have endured his criticism, to have felt the terror and thrill of his drum, to have been dismissed, annihilated, or briefly, surreptitiously, approved of.

Each of these tributes will, no doubt, begin by locating the writer, situating themselves in relation to what Philippe meant to them. This one will be no exception. I was privileged to be part of both the last cohort Philippe taught, and also the first cohort he did not. Which is to say: I arrived at the school in the presence of an ending, and remained in its aftermath.

My weeks spent being taught by Philippe are unforgettable. His eyes were at once slightly unfocused and utterly transfixed; he could bring you down, crush you entirely, with nothing more than an amplified grunt. Once, having struggled painfully to read an excerpt from Georges Feydeau’s 1907 vaudeville farce La Puce à l’Oreille, Philippe simply responded with: “fucking boring, goodbye immediately, come back to the stage only when you have had surgery on your vocal cords to fix your shitty voice.”

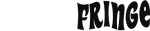

It was a harsh, albeit valid, point. I was terrified that my classmates would no longer want to work with me, at the risk that I would jeopardise their time on stage. I needn’t have feared – Tara, with whom I ended up working for that week’s presentation, invited me to open for her show at the Edinburgh Fringe the following year. And weeks later, when I recounted what Philippe had said to me on that day to those who had been in the room, none had any recollection of it at all.

Perhaps this exemplifies the impulse many of his former students feel to recount their personal stories of Philippe. He entered each student’s inner world differently, establishing a complicité that was intimate and particular. It moved like a private current within the room, a subtle field of attention and energy that connected teacher and student in ways others could sense but not fully access.

This does not mean that Philippe’s teaching should be mythologised without question. His cruelty seemed, at times, real. His insults could land unevenly. For many, the line between provocation and harm was hard to locate. Loving the work, and cherishing the memory, does not require denying this. Still, Philippe undoubtedly left an indelible mark on those who experienced being in his presence.

I imagine that his school has always been an organism, shaped, perhaps, as much by who was in the room as by who was at the centre of it. L’École Philippe Gaulier brings together students from all walks of life: all ages, nations, mother tongues, levels of education, degrees of lived experience. There is no single profile, no shared biography, no obvious reason these people should find themselves in the same room. And yet, what every student has in common is this: that here, now, the time is right for them to be in a small French town an hour south of Paris – at clown school. Some arrive through accident, some through desperation, some through an unshakeable and indescribable impulse. Many have come late to performance; others arrive already accomplished elsewhere. Whatever they bring with them, be it grief, arrogance, exhaustion, or hope, it is placed, very quickly, under the same unforgiving light.

This is what Philippe built. Not merely a school, but a community, one which is dispersed, unruly, and alive. Former students are scattered across the world, across disciplines, across lives that may look nothing like performance from the outside, yet remain shaped by this shared experience. The grief being felt at this moment, in the wake of Philippe’s passing, moves unevenly but unmistakably, across borders and time zones, linking people who may share no language except the memory of a room and a drum.

I realised today that the vast majority of people with whom I am in contact each day are themselves tied to Philippe and his school. Some, I studied with in those rooms in Étampes across two years – many of these remain my closest friends. Others are former students who later became my teachers. Some I met in entirely different contexts – in Australia or the UK; through writing, through study, through performance – and yet we recognised each other almost instantly, bound by the shared experience of that training.

What will come of the school remains to be seen. There are those who argue that without Philippe sitting in the centre, there is no point in attending. But I feel this misunderstands what the school has become. It also fails to recognise the inimitable, frightening, and truly extraordinary Michiko Miyazaki Gaulier – Philippe’s wife, a former student and current head of the school – whose command of a room is absolute. She can tear one to shreds, taunt the notion of expulsion and, later that same day, cook a student a personalised, allergy-safe soup – as I can personally attest. Under the tutelage of Michiko, alongside Carlo Jacucci – a man who seems to speak only in riddles, who is at once whimsical and cutting, generous and merciless in precisely the right proportions – Susana Alcantud, Dain Rubin, and others who honour Philippe’s pedagogy, l’École Philippe Gaulier is not a relic. It is a living institution, and it will last for as long as they choose to sustain it.

Philippe wrote in his book The Tormentor: “I teach my students that they are children of the speed of light and the rotation of the earth … I teach that the place of the actor is situated somewhere at the precise spot which the violent winds will soon move.” This, he most certainly did. He taught us that nothing is still; that position, success, failure, even certainty, are provisional. Winds shift, and one must remain alert enough, light enough, to move with them.

The drum may have fallen silent in one sense. In another, it is already sounding elsewhere.